Ahistoric Idiocy

History cranks and fiends, I promised myself I would send fewer newsletters about George Washington et al., and I was doing so well! Just last week, I was content to tweet about, as a friend put it, The New Yorker’s nothing burger of an article, “Did George Washington Have an Enslaved Son?”

I cannot say the same about two peas in a maggoty pod: Senator Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) and Bushrod Washington, George Washington’s nephew and heir.

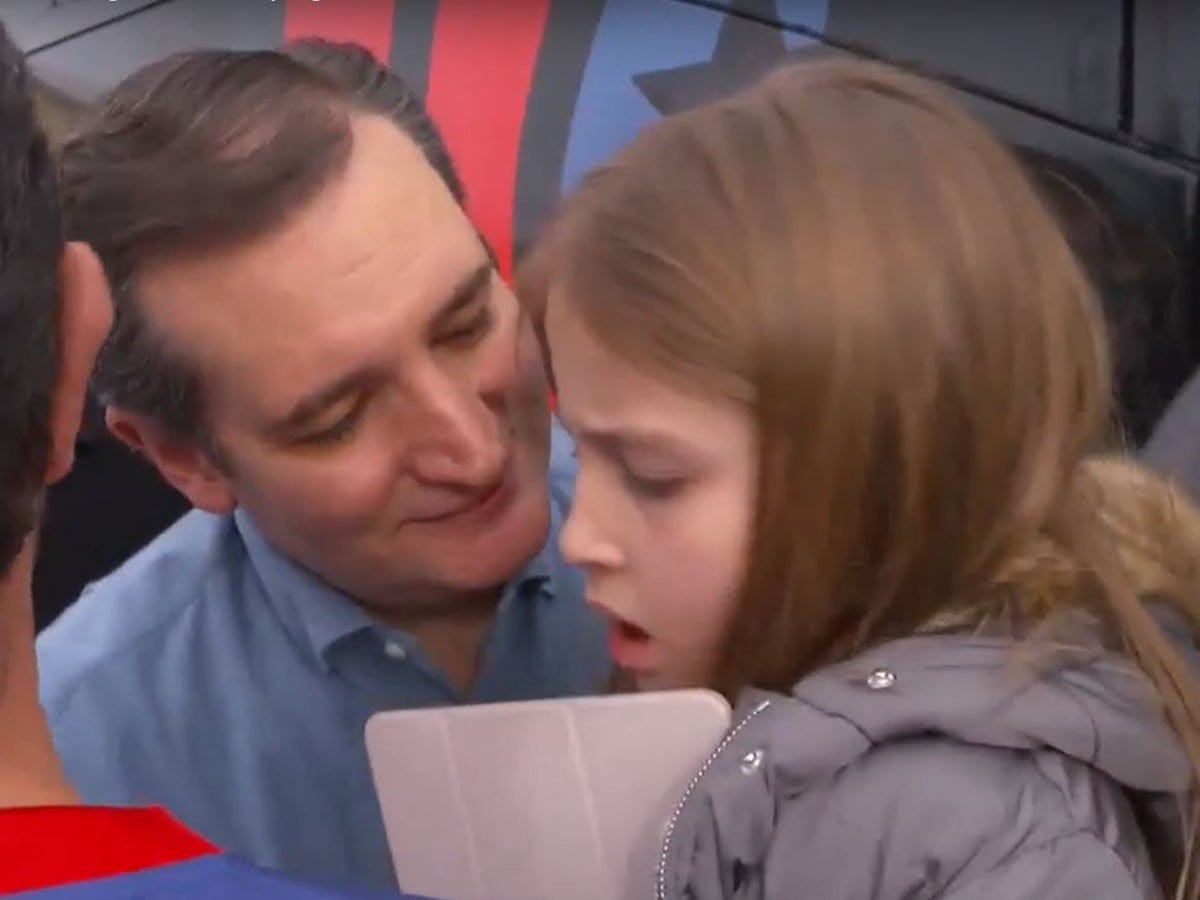

During yesterday’s Senate confirmation hearing for Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, Ted Cruz —who has been called “Lucifer in the flesh” by members of his own party (and likely far worse by his children)—expressed nostalgia for an era in which white men had complete power over anyone who wasn’t a white man. Why would a political operator such as Cruz use Jackson’s historic nomination to ask substantive questions when he could instead draw attention to his own ahistoric idiocy?

“Supreme Court confirmations weren’t always controversial,” Cruz said. “In fact, Bushrod Washington, when nominated to the Supreme Court in 1798, was confirmed the very next day.”

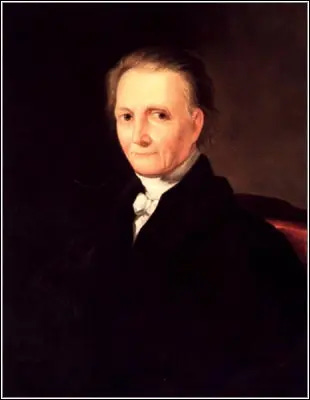

Bushrod, who had already been serving on the Supreme Court for a month, was indeed confirmed in 24 hours. Was it because he had distinguished himself as a jurist courts? No. Like Justice Amy Coney Barett, Bushrod’s first day in the Supreme Court was his first day as a judge.

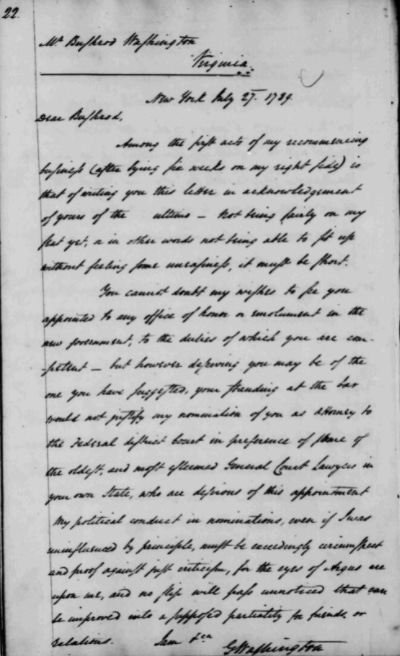

Bushrod had asked his uncle for an appointment. As I wrote in You Never Forget Your First, Washington was fine with low-level nepotism. Prior to this request, he made another nephew, Robert Lewis, a secretary. Lewis could learn on the job without doing much damage, but a court appointment was of great consequence. Washington explained as much in a letter to Bushrod (emphasis my own):

You cannot doubt my wishes to see you appointed to any office of honor or emolument in the new government, to the duties of which you are competent—but however deserving you may be of the one you have suggested, your standing at the bar would not justify my nomination of you as attorney to the Federal district Court in preference of some of the oldest, and most esteemed General Court Lawyers in your own State, who are desirous of this appointment[.] My political conduct in nominations, even if I was uninfluenced by principle, must be exceedingly circumspect and proof against just criticism, for the eyes of Argus are upon me, and no slip will pass unnoticed that can be improved into a supposed partiality for friends or relations.

Washington wouldn’t give his special little boy everything he wanted, and he didn’t need to. The connection was enough, and Bushrod knew how to work it. When he inherited Washington’s papers (and later Mount Vernon, his beloved home and forced labor camp), Bushrod didn’t protect them. He handed them out to friends and colleagues, and libraries have been trying to get them back ever since. On occasion, the recipient acted as Bushrod should have: Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, to whom he gave one of my favorite primary sources, Washington’s furiously annotated copy of James Monroe’s tell-all, donated it to Harvard.

Another thing that more than half of the senators who confirmed Bushrod liked about him? He was, like them, and like his late uncle, an enslaver. When he became the master of Mount Vernon, he brought 79 enslaved people with him. Fearing they had been “visited by some unworthy persons,” (also known as “people who believed in emancipation”) Bushrod wrote to the editor of the Niles Weekly Register, who suggested that he would, like Washington, pave the way to freedom in his will. He did not, and he made sure those 79 people knew his intentions, too. Dr. Lynn Price Robbins, a former editor of the Washington Presidential Papers at the University of Virginia, wrote an excellent blog post about this (again, emphasis my own):

[Bushrod] demanded that talk of future freedom—a rumor that had made its way throughout the estate—cease immediately. The enslaved individuals responded by attempting to seize the freedom denied them and planning their escape. However, their fate became even more troubling. When Bushrod discovered the plot, the ACS [the American Colonization Society, of which he was the founding president] did not encourage his disobedient slaves to emigrate to Africa. Rather, he sold 54 of them, sending them down to the Deep South in Louisiana—a punishment to be dreaded. Bushrod Washington died in 1829 and kept his promise not to free his enslaved workers.

The Mount Vernon website lists what Kellyanne Conway would have called “alternate facts” in its description of the devastating event:

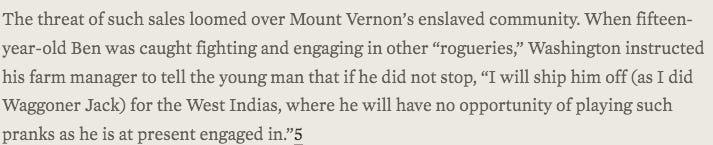

There is another glaring error in Mount Vernon’s description above: Washington most certainly sold people he enslaved for the same reason his nephew did—as punishment for attempting escape. See Mount Vernon’s page for Tom, whom Washington sold in 1766, a decade before the founders took up arms for their own freedom:

I’d trust the Washington Papers over Mount Vernon any day. (I alerted them to the error this morning but it remains uncorrected.)

And about that New Yorker story? I consider the Ford family’s oral history integral to the story, but most experts, including myself, think Washington was sterile. And many of us suspect that Bushrod was West Ford’s father, but the Ladies of Mount Vernon have denied Ford’s descendants access to Washington’s DNA, so we may never be certain.

See you in soonish! I’m working on my next book and a long essay (sorta like Jane Grant) for you. In the meantime, you can find me on Twitter and Instagram and my books, as well as others mentioned on SMK, on Bookshop, Amazon, and your local bookstore or library. If you’d like me to sign or personalize my books, purchase copies from Oblong. If you have a question or comment, send it to studymarrykill@gmail.com.