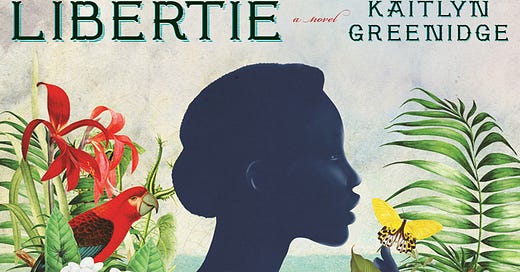

I asked Kaitlyn Greenidge to do a newsletter takeover in celebration of her latest book, Libertie. A couple of years ago, I met Kaitlyn in a pie shop that no longer exists, and we talked around the h…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Study Marry Kill to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.