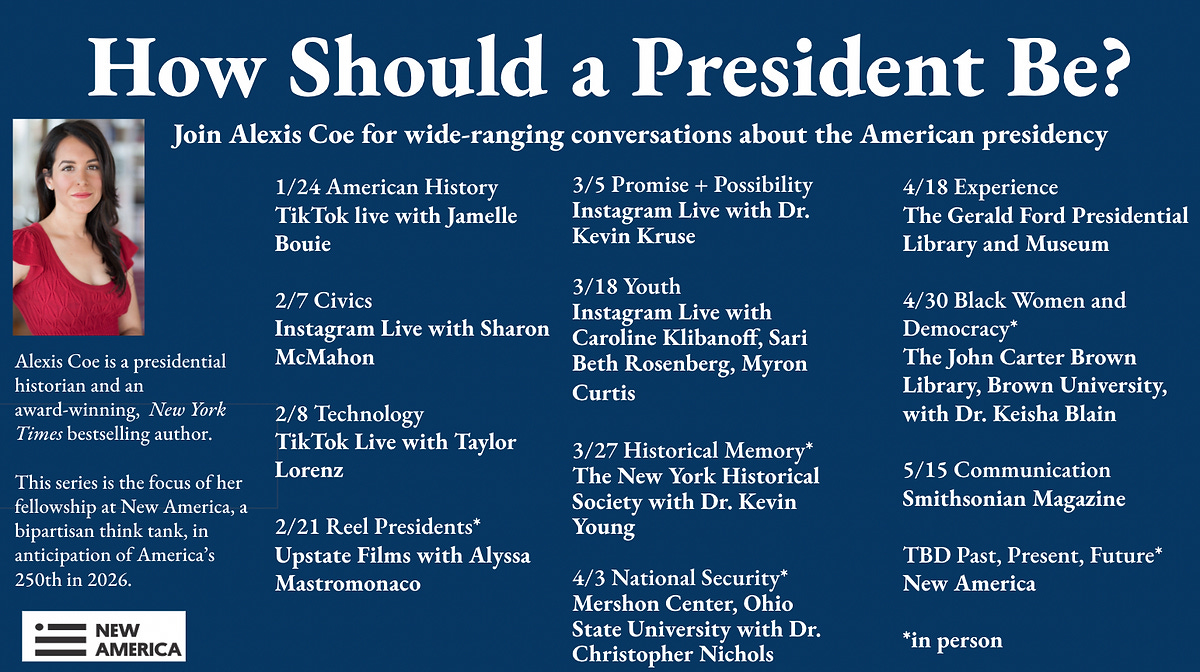

UPCOMING “HOW SHOULD A PRESIDENT BE” EVENTS:

Monday, March 18th, 7pm. Instagram Live. I’ll be discussing the president and future/young voters with special guests: Sari Rosenberg, a high school history teacher and contributor @pbs @newshourextra; Myron Curtis, an AP US History & AP African American Studies teacher; and Caroline Klibanoff, the Executive Director of Made By Us–and a fellow fellow at New America.

Wednesday, March 27th, 6:30. The New York Historical Society. An in-person panel discussion about historical memory and reckoning featuring: Kevin Young, the Andrew W. Mellon Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and the former director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Gisela Perez Kusakawa, the executive director of the Asian American Scholar Forum (AASF); and David Silverman, a professor of history at George Washington University and the author of several books on Native American, colonial American, and American racial history.

YOUNG AND RESTLESS

I lost my voice last year, and with it, the chance to host Mattie Kahn’s book launch at the Strand (thanks again for stepping in, Charlotte Alter)—but she gave me a second chance. In anticipation of Monday’s Instagram Live on the president and America’s young/future electorate, I revisited Young and Restless, and Mattie was kind enough to my questions.

On a related note, Glamour became an APUSH website under Mattie’s tutelage:

Alexis Coe: You became frustrated by the dearth of genuine intellectual interest when it came to young women in history while you were a full-time journalist, and it inspired you to write Young and Restless. Do you remember when you realized that there had been no women presidents?

Mattie Kahn: When I was a kid, my parents would bring us back interesting placemats from business trips. How these became the souvenir of choice, I’ll never know. At some point, from Washington, I’m sure, one of them delivered a placemat emblazoned with the faces of all the presidents. What a shock it was to look down from the Cheerios I was eating and see not a single woman there.

Another memorable moment: My mother is Canadian and we spent most school vacations in Toronto, visiting my grandparents. I remember a distinct thrill when I realized that a woman’s face was on their dollar bills. It was of course Queen Elizabeth’s. Not quite a lesson in democratic leadership, but a delight for me as a child, nonetheless.

AC: How did that reality impact the young women you studied? I’m looking at the gap between the promise of a presidency and the reality of one, which is not unlike the gap between girlhood and womanhood. Did you see a shelf life to young women’s activism that differed from youth activism in general in the women you studied? Does that difference still exist?

MK: Many of the women and girls I cover in the book had low or no expectations for national leadership. Anna Elizabeth Dickinson is somewhat of an exception. She was born before the Civil War and became a passionate orator advocating for abolition. After the war broke out, she toured the Union, delivering barnstorming speeches to help elect Republican candidates. At 21, she became the first woman ever to address the House of Representatives. Abraham Lincoln entered the chamber while she spoke. A different kind of woman would have complimented the President of the United States. Dickinson tore into him. She wanted him to go further and she said so.

Would Dickinson herself have liked to be president? We can’t know. After several massive tours, she lost her luster with the public. She outgrew the precociousness that made grown men perk up and listen to such a firebrand of a teenage girl. She tried to act, thinking that the stage—minus a podium—might become another home for a woman with an opinion. It didn’t work out. Young men who become activists, especially in the decades before feminism and the civil rights movement, could translate their skills and ideals into careers. Young women did not have that option. Adolescence was a sliver of a window in which to be heard; their speeches were just enough of a spectacle to gloss over gender expectations. When their charm and charisma became less cute, their voices became less tolerated.

The fact that women can have careers now of the kind that would have been unthinkable to Dickinson has changed things. Young and Restless includes some agonizing stories, but I want to be clear that there’s been tremendous progress. That it feels so inadequate is a measure of how much farther we need to go. The young women I spoke to for the book are worried about some of the same dynamics that crushed Dickinson. They’re afraid that they’re most valuable to movements now, when they’re photogenic and hopeful. They still don’t have as many reliable models of leadership as they should. Young men take action, and they can look to millions of grown men who were rewarded for it. Yes, the difference still exists.

AC: If you had five minutes to brief President Biden on a young woman from your book, who would you tell him about?

MK: I still think often about Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, a Chinese immigrant who became a loud advocate for suffrage. She lived in New York at a time when anti-Chinese discrimination was rampant and encoded in the law itself. Her parents had been able to move to the United States because her father was a minister, a narrow carveout in xenophobic immigration policies. Still, she was a star student, got into Barnard, and dazzled the suffrage movement with her vision for change. She was such an exhilarating speaker that newspapers wrote crowds left her appearances “mabelized.” She led thousands of people up Fifth Avenue in a suffrage march in 1912.

Lee pushed for reform that she had no expectation would enfranchise her. She believed in the principle of the women’s vote and wanted more of it, even if her immigration status excluded her. She went on to become one of the first women and the first Chinese woman to earn a PhD from Columbia. Her friends were sure she would rise to prominence in Chinese politics or otherwise embark on an exceptional career in academics stateside. But her father died, and the Depression hit, and she ended up taking over his church in Chinatown. Was she satisfied? Did she feel fulfilled? We don’t know.

For years, I’ve wanted a different ending for Mabel—some conclusion that feels commensurate with her talents. To me, her example illustrates that it’s not enough for a girl to be right or to be persuasive or to have vision. She has to have options. Someone in a position of power should know that.

AC: Would you tell Trump about the same young woman?

MK: Would he listen? I’d quote Claudette Colvin, who refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Alabama nine months before Rosa Parks did the same thing. Later, she was grilled in court; prosecutors demanded to know who’d put her up to her action, since it seems so implausible to them that a teenage girl was self-motivated. Colvin replied on the stand: “Our leader is just we ourself.”

AC: I hate being asked hypotheticals and yet I never miss an opportunity to ask them! Pretend Gerald Ford was right when he predicted that a woman would be president circa 1980. How do you think that would have influenced the women you write about?

MK: I hate answering questions with, “It depends,” but of course it does! Which woman became president? What were the circumstances of her election? Was she a vice president who inherited the office? An outsider candidate? A Republican? A Democrat? A significant number of the women and girls I spoke to for the book who are activists now feel disillusioned with mainstream politics; would a woman in that office have restored their faith in what politics can achieve? It depends! What did she do with the platform?

What I do think is true is that if we’d had a woman president—no matter her particular credentials or path to leadership—we would see more women run for office. How it might have influenced the women I wrote about is hard to know, but it would have shown them that that kind of power was within their grasp.

AC: 2024 is an election year. What can we learn from these young women? Do you see a connection between the women you write about and modern (or future) presidents?

MK: I wrote this book long before Barbie swept theaters and Taylor Swift and Beyoncé swept stadiums. But those cultural phenomena validated what I knew from working on this book: that girlhood is a profound cultural force, but also that its trappings and aesthetics are no replacement for legislative power. There are elements in our culture that make girls feel like they matter, but they can’t compensate for the real barriers and realities that keep girls stuck in place.

Instead of just taking our consumer cues from girls, I’d like to see us work harder to include them in political conversations—to make them feel like it’s not just their dollars that move industries, but their opinions and their aspirations.

Young and Restless records the stories of girls who have tried—with varied levels of success—to retain the advantages of girlhood even as grown women. I hope to live to see a future president who pulls off the transition.