Confession of a Feminist II

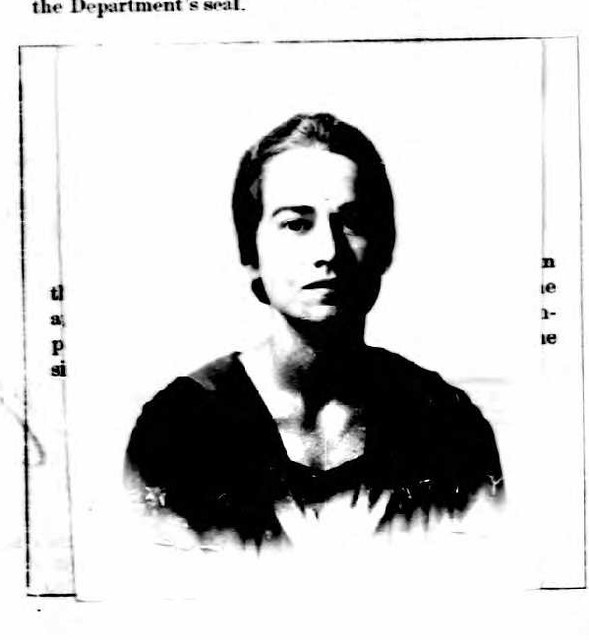

A serialized biography of Jane Grant (1892-1972), first woman reporter at The New York Times and co-founder of The New Yorker

This Week’s Schedule

Saturday: A Book I Won’t Write; or, A Book One of You Should Write—Ideally Before 2025

Sunday: “The gentle art of being weak”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Study Marry Kill to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.