Confession of a Feminist IV

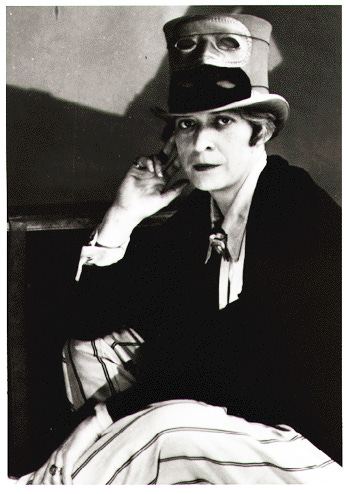

A serialized biography of Jane Grant (1892-1972), first woman reporter at The New York Times and co-founder of The New Yorker

This Week’s Schedule

Saturday: A Book I Won’t Write; or, A Book One of You Should Write—Ideally Before 2025

Sunday: “The gentle art of being weak”

Monday: “Harold W. Ross for himself, and Jane Grant separately and independently”

Tuesday: “Your work is not comparable to mine in volume or complexity”

Wednesday: “We must not forget that we are dealing with a woman”

Thursday: “Confession of a Feminist”

Friday: “Ross and the Invisible Me”

Saturday: Sources and Open Discussion

“Your work is not comparable to mine in volume and complexity.”

When Harold Ross proposed launching a “high class tabloid” to his wife, Jane Grant, she vetoed it outright, as she did his second idea, “the real story of the shipping news.” Grant “did a good deal of prodding,” reading Punch, Harper’s Weekly, Life, The Smart Set, and American Mercury for inspiration while trying to figure out why Judge, the humor magazine he was an editor of, was failing so spectacularly. Ross’s sense of humor had made Yank Talk a success, but readers in postwar America wanted something different than soldiers at war. “Ross had great humility then,” she recalled. “He assured me he’d try anything I decided upon.”

Ross finally brought her something she could work with: A weekly arts and humor magazine about New York. They could ask regulars at The Wit’s End to contribute, and raise local money to support the magazine. And she would have to work at least two jobs to support him. They planned to live off her Times paycheck, and when she wasn’t at the paper, she could work on the magazine handling whatever might distract or derail Ross, which was a lot.

How would they pay for it? Grant worked publishingexecutives for their business models and came up with a $50,000 self-financing plan that would allow them to remain in control. They liquidated their assets and took out a second mortgage, but they were still only halfway there. They’d need an investor, and Grant had Raoul Fleischmann, of the Fleishmann’s Yeast company, in mind. Grant liked his wife, Ruth, who seemed to attract “our more imposing male guests though they were often deflated by her crisp remarks.” At Wit’s End, she once told Otto Khan that “opera bores me.” He stood up and announced, “Madam, I am the director of the Metropolitan Opera. I bid you goodnight.” They also had a country home, all of which made them “a fine addition to our group.”

She hadn’t considered Fleischmann as an investor until they went to the baking heir’s home for bridge. She didn’t play, but Fleischmann, “always the charming host,” marvelled that her friends, “these amusing and interesting people,” made him feel alive, something the family business never had, and asked about their plans. She’d found the money, she was sure, and dropped enough hints about the magazine to leave Fleischmann begging for more. Grant demurred, brokering a proper meeting between him and Ross in the sober light of day.

It was a disaster. “I couldn’t understand why he came to me with such a dull idea,” Feischmann complained to Grant. She’d made a miscalculation, but it wasn’t the concept or the investor. “Slowly I dragged the truth from him,” and it wasn’t good. He’d pitched a totally different publication, and done so poorly. “Ross was often wife-deaf in those days,” she wrote. “I frequently had trouble getting him to carry out a plan we’d decided on.” They practiced the original pitch for a week and set another meeting. This time, Ross followed the plan, and it Fleishchmann sent Grant $25,000. He also agreed to provide free office space in a building he owned on 45th street.

In early 1925, Grant hand-delivered previews of the first issue to every important person she knew in New York. They’d toyed with different titles — Manhattan, Our Town, New York Weekly, New York Life — before press agent John Toohey suggested The New Yorker at the Round Table. They named friends to a Board of Editors, including Broun, Dorothy Parker, and others Grant described as “window-dressing names.” Ross called it “the only dishonest thing I ever did.” The magazine made an impression, but many thought it was doomed to fail.

The timing didn’t help. The first issue of The New Yorker landed in newsstands alongside the 200th-anniversary edition of the New-York Gazette, the city’s first weekly. By comparison, The New Yorker, full of weak humor and inconsistent coverage, looked “like it had been made up by the office cats knocking over wastebaskets,” managing editor Ralph McAllister Ingersoll admitted. “How the hell could a man who looked like a resident of the Ozarks and talked like a saloon brawler set himself up as the pilot of a sophisticated, elegant periodical?” wrote the playwright Ben Hecht.

The money ran out in six weeks. Grant raised more during a cold-calling blitz, talked Fleischmann to matching it, and then focused on personnel. The launch made it impossible to deny that the magazine needed a full-time publicist and new writers. She she sent Ross to recruit Murdock Pemberton.

“God dammit, Jane says you ought to be our art critic.”

“That’s the craziest idea yet,” said Murdock. Murdock was not a pusher.

“I thought so, too, said Ross, unflatteringly.

A week later, Ross saw Murdock again at lunch. “God dammit, Jane still says you ought to be The New Yorker art critic. How about it?” he said. Murdock was the art critic for seven years.

While Ross worked the Round Table, Grant tapped Lucy Stoners. Lois Long wrote “On and Off the Avenue,” and when she took over “When Nights are Bold,” renamed it “Tables for Two,” something Grant and Ross rarely enjoyed. She asked Janet Flanner to write a biweekly column, “Letter from Paris,” based on the ones she was already sending Grant. Flanner agreed, but was unaware Ross had assigned her a pseudonym until she saw the byline. She wrote to ask which of “the rather objectionable Genets” he’d chosen. He never responded. She later gathered he knew none of them. “To his eyes and ears it seemed like the Frenchification of Janet.”

“I have never worked harder in my life,” Grant wrote. She was still writing for the Times and active in women’s rights. “Ross kept me generously supplied with homework—manuscripts to read, contacts to make and keep up, which he had no time or wish for, and various other assignments.” She figured out how the Times subscriptions worked and then modeled a campaign for The New Yorker.

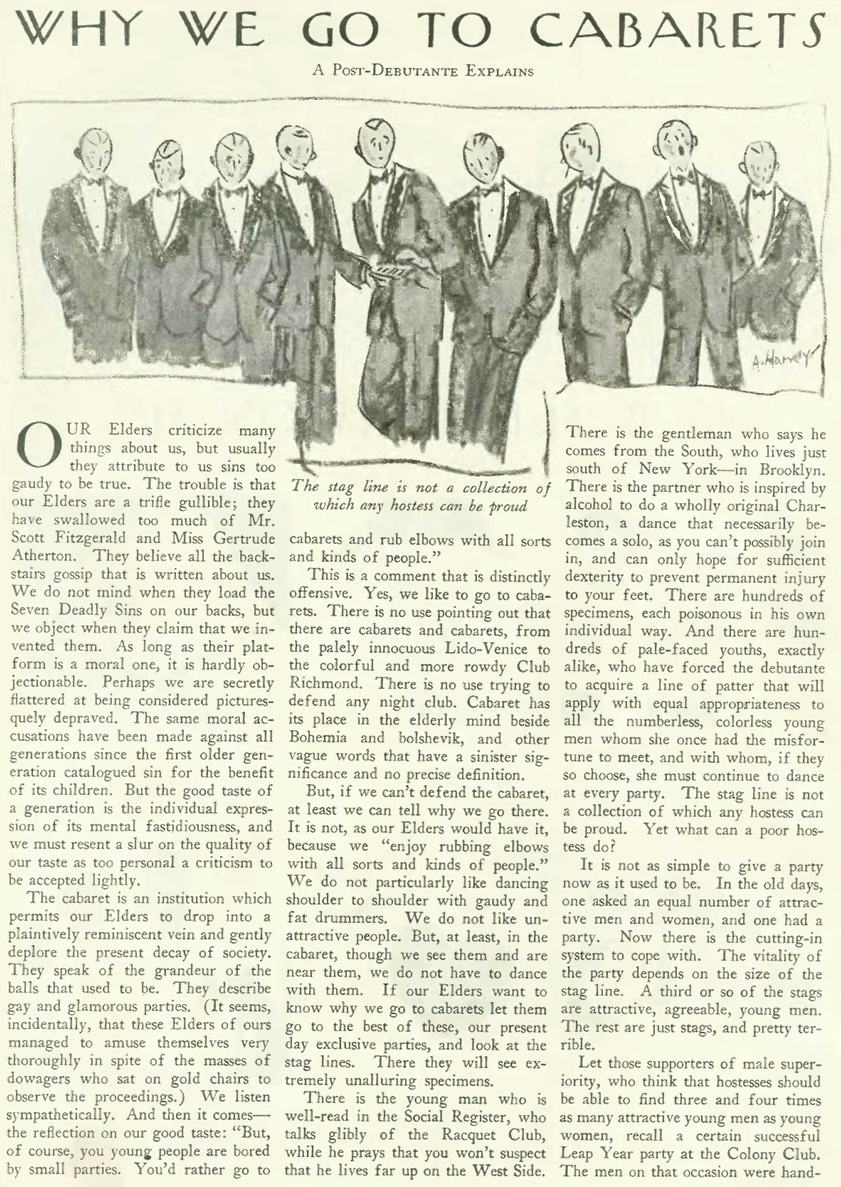

Not that he took all of her suggestions easily. They fought over “Why We Go to Cabarets: A Post-Debutante Explains.” Ross dismissed it as the stuff of society pages. Grant saw nothing but “promotional value” in an essay written by Ellin Mackay, daughter of the president of the Postal Telegraph Company. “‘I’m afraid it won’t be any good,’ he said defensively, for he liked Ellin and preferred to put off rejecting it. ‘Even if she has written it with her foot you can’t turn it down,’ I protested.” Grant won, leaked it to friends, and created a false sense of urgency. “Each of the three papers—the World, the Times and the Tribune—believing they had a beat, ran a spread on their front pages,” she wrote. The afternoon papers followed the morning papers, as did domestic and foreign news services. It was the first time the magazine sold out.

By the time the November 28, 1925, article hit newsstands, rebuttals were being published across the country. That was the first time James Thurber, the humorist, remembers hearing about the magazine. Park Avenue residents rushed to subscribe, and that led to ad revenue that rivaled national publications. Even Hollywood took notice, and wired an offer of $50,000 for the movie rights. Ross warned Mackay “they only want to exploit your name,” and “seemed not to realize that we were doing the same thing.” She turned down the offer.

Three years after launch, Grant had worked tirelessly, and TheNew Yorker was profitable, but Ross only seemed to appreciate the outcome. He was hard on his staff—editorial feedback included “Hogwash,” “Fix,” “tinker,” “make better,” and “Who he?”—but he was hardest on Grant, sending her much notes about her faults. When Thurber, who had become a regular contributor, announced he was in love, Ross asked only one question: “Is she quiet?”

She marked Christmas 1927 as the beginning of the end. Perhaps it had started to deteriorate over the summer, when Ross’s father died. Then his chronic ulcers worsened. He fixated on Woollcott, who had withdrawn his name from the magazine’s Board of Editors right before the publication had been announced. Neither Ross or Woollcott were pleased by her response to their troubles, no matter what that response was. “Most of the time I felt as if I was perched on the edge of a setting volcano,” she wrote. “I felt [Woollcott] played a big part in making our marriage impossible.”

“I knew, at last, that I must subordinate all thought of my career and even my happiness.” The Times was a financial necessity, but none of her other activities outside The New Yorker were. “You go through several years of that and you can’t take it anymore,” he wrote her, admitting he’d thought her interest in women’s rights would be a passing phase. Ross was surrounded by a thoroughly modern set, but he was old-fashioned prude. (After his death in 1951, Grant admitted she’d never even seen him naked. He turned off the lights when they had sex, and when the lights were on, he was in a nightshirt or, if he was fast enough, fully clothed.) She cut down the time she spent on the Lucy Stoners and the Club, but that didn’t seem to please him either.

In 1928, Grant suffered a nervous breakdown. “My doctor carted me off to Mount Sinai Hospital, first for observation and then an operation.” She was diagnosed with colitis, a digestive disease. “The only consolation I have is that, at least, I know where you are,” Ross said during his daily visits. But once she returned home, he’d lug his typewriter around the brownstone complaining about the noise, or the lack of noise, or something else. She needed rest, doctor’s orders, and moved to Woollcott’s old room. Ross argued it would be easier if he lived closer to the office, and took a room at a hotel across the street. After “a few of his protracted absences,” Grant took over his more comfortable bed. He was outraged.

“So you’ve appropriated this bed,” he said, thickly.

“Well, it doesn’t seem to be so popular with you,” I countered.

“I’m only an outcast. I’ve no place to go, no place to lay my head,” he moaned with drunken dramatics.

“What about your hotel suite?”

He’d lent it to a friend. Grant, still weak, lost her patience and demanded he “end such early morning disturbances.” She asked for his keys. He spent New Year’s Eve in Atlantic City, and when he returned, suggested they spend more time apart. Perhaps she could take a trip. A long one. He mentioned China.

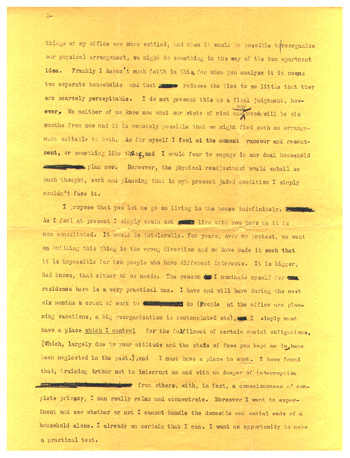

“You are a disturbing and upsetting person,” he wrote to her. Ross preferred “freedom from you” but disliked the inconvenience of living away from home. He thought she would fare better in the same situation because “your work is not comparable to mine in volume and complexity.” He proposed she move out and he return to their home for the indefinite future because, “I simply must have a place which I control.” “I still feel that this is a selfish and unreasonable demand,” she responded, “but by this time you surely know that I want to please you.”

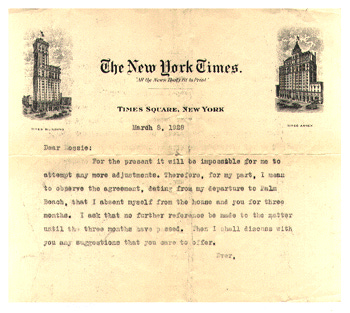

Grant had no more to give. “For the present it will be impossible for me to attempt any more adjustments,” she wrote to her “Dear Rossie” on Times letterhead. Van Anda, still her confidante, suggested a few weeks off. She went to Georgia and Palm Beach and heard nothing from Ross, so she didn’t tell him when she returned. He heard from friends and showed up at the Barclay Hotel, where she was staying, “guiltily hovered over me, trying to justify his behavior.”

He ran hot and cold. They wanted to discuss a separation with their lawyer. “Ross chivalrously bowed out” when he said he could not advise both of them. Then he became convinced the brownstone was to blame for their troubles and her poor health; they went to see an apartment at the Savoy-Plaza Hotel. He asked her to a series of dinners, where they discussed The New Yorker. He invited her to social events. When her attorney said she had to move back into 412 in order to “be the aggrieved one,” Ross stayed in the house. “Our friends were jubilant,” she wrote, but not for long. The lawyers were still negotiating. Neither party tried to stop them.

Grant found him to be far better at divorce than marriage. “Never for a moment did Ross lack consideration,” she wrote. He volunteered to play adulterer in a state that required one party to be at fault. He suggested she take whatever she want from their home and sell the rest, including the brownstone. “I carefully left books I knew he loved, chairs which he favored and, of course, that comfortable bed.” They split the proceeds, and she took just enough to furnish her rooms at the Savoy-Plaza. She was moving into the small apartment they had looked at together.

The matter of the magazine took slightly more negotiation. “I had sacrificed a good deal for The New Yorker,” Grant maintained, and no one disagreed. Ross wanted her to remain involved and invested in the magazine. He signed over 450 of his shares in the F-R publishing Corporation, The New Yorker’s holding company, and deposited the first of a yearly $10,000 dividend payment into her bank account.

At the same time, Ross “objected fiercely” to her attorney’s suggestion that, should the magazine decline in value or fold, he be held responsible for the payment. Without it, the judge was unlikely to grant them a divorce. They had to offer him something in lieu of alimony, the standard of the day. Grant argued it was based on the assumption that a woman could not support herself, yet she’d been paying her own way since she was 18 years old. “I really preferred to get my financial reward from the magazine,” she wrote, and for once, Ross liked the sound of her feminism. He agreed to cover Grant’s annual $10,000 dividend if the magazine couldn’t, and with that, they were divorced. They shared The New Yorker and nothing else.

See you tomorrow! Until then, you can follow me on Twitter, Instagram, and find my books at Bookshop and Amazon.