Confession of a Feminist VII

A serialized biography of Jane Grant (1892-1972), first woman reporter at The New York Times and co-founder of The New Yorker

Thank you for reading Jane Grant’s biography! This is the final chapter. Tomorrow, I’ll send a short note on the project, link to sources, and leave the comments open for discussion. See you then, or find me on Twitter and Instagram.

This Week’s Schedule

Saturday: A Book I Won’t Write; or, A Book One of You Should Write—Ideally Before 2025

Sunday: “The gentle art of being weak”

Monday: “Harold W. Ross for himself, and Jane Grant separately and independently”

Tuesday: “Your work is not comparable to mine in volume or complexity”

Wednesday: “We must not forget that we are dealing with a woman”

Thursday: “Confession of a Feminist”

Friday: “Ross and the Invisible Me”

Saturday: Sources and Open Discussion

Ross and the Invisible Me

Within a couple years of Harold Ross’s death, a slew of books came out about him and The New Yorker. Critics thought James Thurber’s The Years With Ross had a little too much of Thurber himself, but it was nonetheless a bestseller. Jane Grant had given him hours of interviews, and he relied on her memories for background, but he only mentioned her by name once.

She wrote her own manuscript and submitted it to a few editors, but no one bit. They’d tell her to restructure it one way and then, upon seeing the rewrite, another. Or they’d tell her Thurber’s book had much of the same information and, as they all pointed out, was so well-written.

Grant seemed to lose herself in everyone’s notes. “I am doubtful of the wisdom of the change,” she’d write, and then make the change anyway. This Grant was not the one from “Confession of a Feminist,” confident in her abilities and quick to note her successes. It was the author of an unpublished World War II memoir, rejected by editors on the grounds that readers didn’t care about women reporters.

Ken McCormick, the editor-in-chief of Doubleday, thought she needed help from another writer. “A book about Ross and The New Yorker should be sharp and witty,” he told one candidate, and Grant was late getting back to the other. Both men dropped out, and then McCormick did, too.

Other editors wanted her to include more personal details about her marriage to Ross in the book, which was, by the 1960s, very late to market. Grant revised the manuscript again and again, only to be told that it still wasn’t quite right. The “book really belongs to you, and to no one else,” wrote Alfred Knopf, Jr., one of the founders of Athenaeum, at the end of his rejection letter.

Grant’s husband, William B. Harris, urged her to keep trying, and in 1967, almost a decade after she’d started on the first draft, she found a buyer. “We are looking forward to your cocktail party,” Eugene Reynal, who ran his own publishing house, scrawled on a piece of paper attached to a contract. Your cocktail party. Reynal knew he wasn’t just buying an ex-wife’s tell-all. He was buying into her reputation. She would do a better job of marketing, publicizing, and selling her own book than his staff ever could. “I think on the whole it does not need a difficult editorial job,” Reynal assured her, offering along with a few, vague editorial suggestions: cut a chapter, work on others, and add a conclusion. He was eager to release it as soon as possible.

Janet Flanner agreed to write the introduction but urged Grant to go with a more exciting title, favoring Gluttons for Punishment or the apt Ross and the Invisible Me. In the end, Grant stuck with the rather staid Ross, The New Yorker and Me, which she dedicated to Harris, “without whose constant prodding it would never have started, and to all the remarkable people—editors, contributors and businessmen—who have worked for The New Yorker, and who have added a new dimension to American letters.”

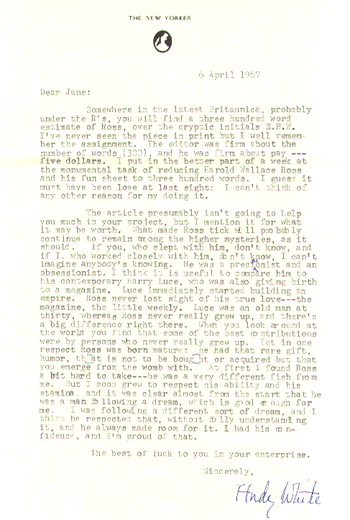

Published in 1968, the book found its best reception in the Times, in a 300-word review that was more of a summary. Many of the other reviews were brutal and often personal. Edward Bernays, a New Yorker board member whom Grant had often been at odds with, wrote in the Christian Science Monitor that she had eked out a “limp look at the wits of the 1920s.” E. B. White, who admitted in a letter to an editor friend at The Atlantic that “I haven’t really read the book—just poked around in it,” didn’t like what he saw. “When she tries to reproduce Ross’s speech, I collapse in a fit of ugly mirth,” he wrote. Harper’s Weekly, staffed by former Ross acolytes, echoed the earlier criticisms from editors but then went much farther: “In spite of the fact that Miss Grant made her living for many years by writing, there is very little literary quality—nor even perception.”

Grant took the reviews in stride, satisfied enough by the book’s existence. But she felt a duty to ensure that more such books were written. One of her fri ends from the Newspaper Club, Ishbel Ross (no relation to Harold), had left journalism and dedicated herself to writing biographies of women. Grant would never write another book, but was inspired to use her own talents in furtherance of the same goal.

Several years earlier, in 1964, she and Doris Stevens, another Lucy Stoner, had established the Harvard-Radcliffe Fund for the Study of Women. Grant directed Reynal to forward all her royalties there, and then she launched a letter-writing campaign that raised $35,000. There was more to come; she’d managed to get the fund worked into a good many wills, or at least extracted promises it would be. Grant and Harris wanted their own estates to fund an endowment for a scholar dedicated to studying women.

Harvard proved to be a challenging partner, less than eager to agree that the study of women should be a legitimate academic pursuit. After the initial donation, Grant, then in her 70s, wrote, “we’re finished with that institution.” It wasn’t the only disappointment.

Special-collections libraries all over the country had been courting Grant since Ross, The New Yorker and Me was published, but their approach was all wrong. Howard Gottlieb, chief of special collections for the Boston University Libraries, wrote to “Mrs. William Harris” about his “magnificent new library,” perfect for her papers. She responded by donating a tall stack of brochures from the Lucy Stone League. Gene Gressley, the director of the Archive of Contemporary History at the University of Wyoming Library, addressed his query to “Mrs. Harold Ross” and received the same package. They all did.

In 1972, at the age of 80, Grant died from cancer. She never settled on a home for her papers, but Harris did. He left almost the entirety of his estate—$3.5 million—to the Center for the Study of Women at the University of Oregon. The bequest was made solely in Grant’s name, his wife of 28 years. It awards $100,000 a year to support research, conferences, and course planning to ensure women are treated as Essential.

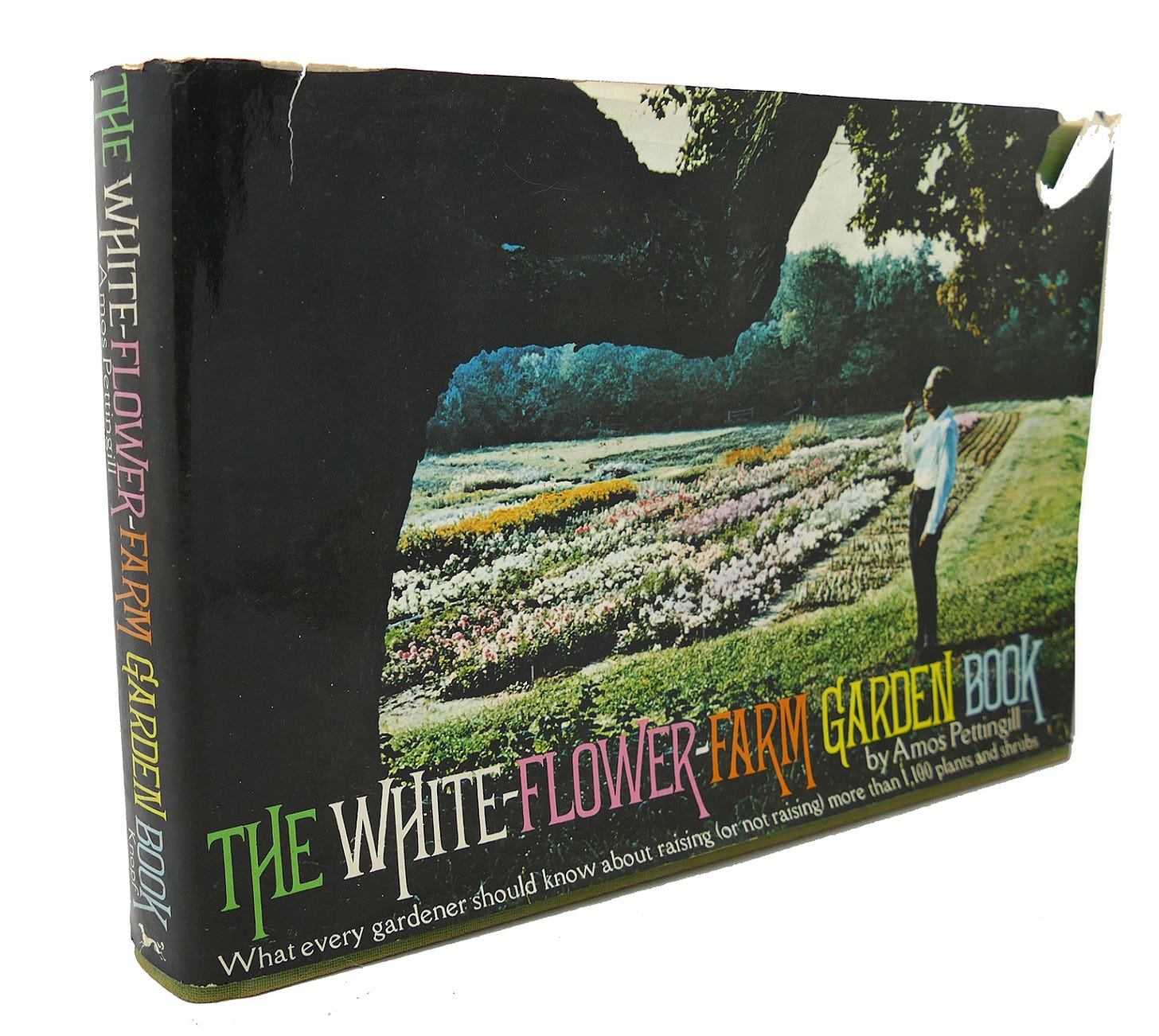

In an obituary in the Times, readers learned that an important woman had just died. Ross made the subheadline, but he and the magazine only appear in a few paragraphs. This is Grant’s story, and it recognizes what she accomplished: The journey from Kansas to New York; becoming “the city room’s first woman reporter”; the Lucy Stoners; reporting “from New York to Hsinking, China”; writing “Confessions of a Feminist”; starting White Flower Farm. A quote from her husband set the tone: “Mr. Harris remembers her as ‘one of the first, real women’s liberationists.’”

In a slip that Grant would doubtless have found very funny, the author of the obituary conflates her with the great Lucy Stone herself: “Throughout her career, Miss Stone insisted on being referred to as Jane Grant, and went so far as to refuse telephone calls to her home in her married name, saying ‘there is no Mrs. Harris here.’”